This spring, I’m teaching a graduate seminar for the first time in four years. At its height, it had 17 people enrolled, although it’s settled down in 14. Given that I’m also teaching an upper-division undergrad class with 24 people, and I need to get more research done than I did last semester, I spent some time over winter break considering a) what work I was going to require of my students and b) what grading that was going to require of me.

As part of this, I did a quick Google search for the syllabi I could find for graduate seminars in geography. Most classes and their syllabi have disappeared into the classroom management system void, but I still found about a dozen from the past couple of years that I could model. I wanted to get a sense of what was required and how it was weighted. Without giving away courses, institutions, or instructors, here are the models I found:

- Participation: 30%

Lead two discussions: 30%

Essay (2500-3000 words, based on at least five readings): 40% - Participation

Evaluation of others (this is in my notes, I’m not sure what it means)

Three 2-3 page reviews of supplemental materials

“Review-and-agenda” paper of 15-25 double-spaced pages with 20 references

Progress reports on the paper

15-minute class presentation on the paper - Participation: 25%

Lead discussion: 25%

Term paper (5000 words): 50% - Participation: 40%

Weekly QAQC paper (quotation, argument, question, connection): 30%

Essay (10 pages): 30% - Participation: 20%

Two exegises: 20%

Lead two discussions: 20%

Either one or two papers, 20-24 double-spaced pages total: 40% - Participation: 50%

Exhibit: 15%

Term paper: 35% - Participation: 20%

Presentation/facilitation: 10%

Four outlines, four reaction papers: 20%

Term paper (4000-5000 words), including peer review: 50% - Participation: 20%

Term paper (12-15 pages)

10-15 minute presentation - Six reaction papers: 33%

Term paper (6000 words or 22 double-spaced pages): 66% - Participation: 15%

Weekly reaction paper and leading two discussions: 20%

Paper proposal: 5%

Term paper (6000 words): 50%

15-minute presentation: 10% - Participation: 25%

Lead discussion: 10%

Weekly reaction paper: 20%

Paper proposal: 5%

Term paper (15-25 pages): 30%

10-minute presentation: 10%

Some thoughts:

- Wow, is that a lot of variation in how much participation counts.

- I thought weekly reaction papers were de rigueur, but only about a third of these classes require them. Is that to save on grading?

- There’s also a lot of variation in length of the term papers, and in how structured their assignments are.

What I came up with based on a combination of these and my desire to keep the volume of grading under control so I could do it in a timely fashion was this:

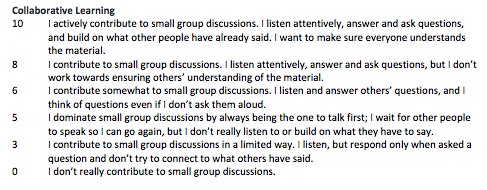

Participation: 15% (self-assessed)

Weekly reaction paper: 25% (started off in the QAQC format, but now is more open)

Lead discussion once in a team of two: 10% (many grad students have never led a class discussion, so I thought partnering up would help)

10-minute presentation on a book not on the syllabus: 10% (that way we get to hear about a lot of different books that are out there while primarily reading articles)

Short term paper 1: case study of an activist organization or issue: 20% (to apply theories from class to a real-life case, but also to understand that “mobility justice” predates academia)

Short term paper 2: review-and-agenda paper: 20% (to identify what literature is most useful for thesis/paper projects)

How does this compare to your recent graduate seminars, either as a teacher or a student?