When I was an assistant professor, I started tracking how many hours I worked per week. I started this to make sure I was spending enough time on what I was “supposed to.” (And because my spouse and I had already been tracking our work and housework hours to make sure my long commute in California was adequately compensated, but that’s for another post.) I don’t know that it made me change my habits at all, but it seemed to average about 40 hours per week during the school year and 20 hours per week in the summer.

After I was tenured, I kept keeping track out of habit, but then decided at some point to stop. And then after becoming a full professor, I felt like I was doing no research at all compared to teaching and my new service responsibilities. So this fall, I got a nifty time-tracking app set up, and I’ve been keeping track of everything I do.

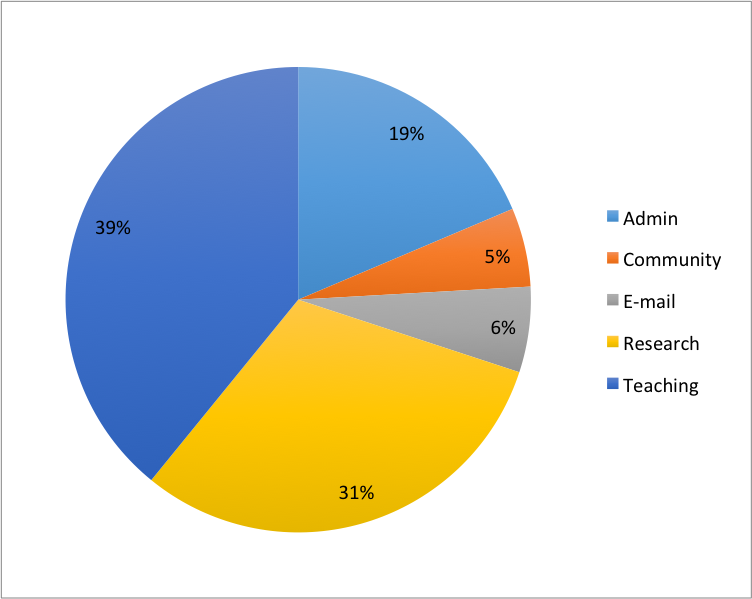

I have five broad categories: Research, Teaching, Administration, E-mail, and Community (departmental coffee hour, colloquium, etc). I broke out e-mail because I wanted to see how much time it specifically took, not just reading messages but dealing with their contents. I averaged 43 hours of work a week in the fall semester, broken down like this:

That’s not bad, right? Research is almost a third of my time, teaching is over a third of my time, and everything else is a little under a third. I mean, research is the only thing that’s important as far as The System is concerned, so that piece of the pie should be much bigger. But overall, it looks pretty balanced.

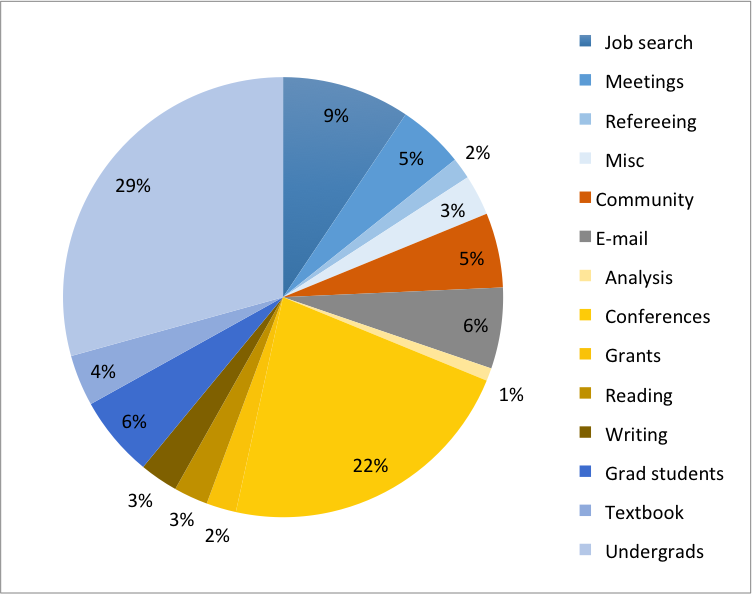

However. When I record my hours, I break them down into specific activities: meetings, classes, large service commitments like being on the university’s climate action plan team, grant writing, etc. When we look at that pie chart, it’s a little different:

Half of the admin came from chairing our tenure track job search. That’s understandable, and I’d gladly do it again (if only because it meant we were hiring again!). Teaching is almost entirely my two undergraduate classes (of which the team-taught one was almost exactly half the hours of the other one), plus meeting with grad students and working on my transportation geography textbook.

The real shocker was research. About 70% of the time I had marked as research was traveling to or attending conferences. I went to three: Regional Studies Association in Montreal; Transport, Traffic, and Mobility in Paris; and the West Lakes Regional Meeting of the AAG in Cedar Falls, IA. Which means a tiny 1% of my time went to data analysis, 2% went to grantwriting (and that was more than normal, since I’m on sabbatical next year and was applying for a lot of fellowships), and 3% went to reading books and articles in my field. A measly 3% went to writing, which again, is the only thing besides grantwriting that really matters according to R1 university standards.

So what am I going to do with this information? Well, since my role in our job search is largely done, that will free up about 4 hours a week. E-mail didn’t take up as much time as I feared. Teaching will take much more time, since my grad seminar will require a lot of hours of reading and grading. I only have one conference in the spring, although since the AAG takes up a whole week, I’m expecting the conference hours will be about half of what they were in the fall. Now, that’s not all directly transferable to additional hours for other things: I’m not going to replace my 26-hour journey to Paris with 26 hours of writing, for example.

It got me thinking about conferences, though. I did get some great things out of going to Paris, including getting to know people with whom I’m co-sponsoring sessions at AAG, learning about new books that are coming out, and motivating myself to make at least a little progress on my research. But is that worth the time? There’s a huge debate right now about academics flying to conferences in an era of climate change, which I’m pretty firmly ambivalent about but am getting very interested in the discourse. (Again, for another post.) What I learned from analyzing my hours like this is that there’s another aspect to deciding whether or not to attend a conference. We all have only so many hours in the week, and hours spent in transit or in paper sessions are hours we’re not working on our own research. Obviously, we get ideas from hearing other people’s work, including potential collaborations; I’m working on an article right now with someone that came about because we’ve attended multiple conferences together. But at least for an introvert like me, maybe I need to be more careful about the conferences I choose: what am I going to get out of going there in person? Is it worth my time?

Have you tracked your hours? Made modifications to your schedule as a result? Or do you not want to monitor yourself like that?