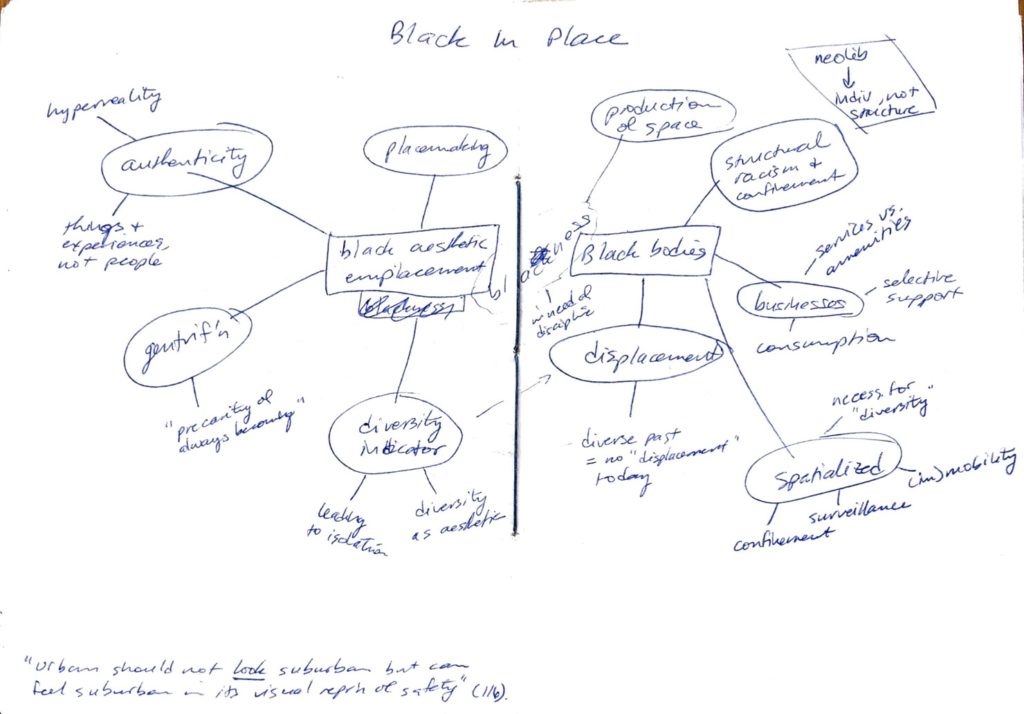

I got this book because I saw Natchee Blu Barnd speak at the AAG in 2019 and was really interested in his work. I’m trying to read more about settler colonialism and geography, in part because of a course I’m teaching on U.S. regional geography, but also because I’m trying to read more by indigenous geographers. Given the full title–Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism–I thought it would be about strategies within the discipline of geography. Instead, it was about the geographic strategies that indigenous people use to resist, which was just as interesting.

I love geography studies that focus on the mundane, taken-for-granted aspects of life that nevertheless have a strong place/space component. In this case, that includes street signs, license plates, and hometown parades. Brand’s detailed analysis of the communities across the U.S. with Native American-themed street names, both in and outside of reservation spaces, does a nice job of showing the value of looking at something so quotidian with a fine parsing of meaning and implications. There’s also an interesting chapter on Satanta, KS, and the descendants of Set-Tainte, for whom the town is named, that gets at some of the complexities of a White town trying to honor Native Americans while the Kiowa people try to honor their ancestor.

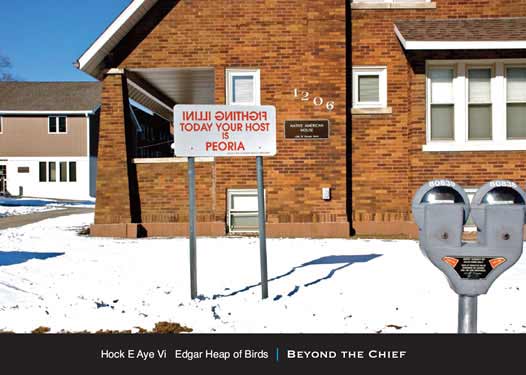

Brand then switches to looking at indigenous artists who use maps and other geographical elements in their work, first in a chapter on prints and paintings, and then in a chapter in installation art. I was glad to see Edgar Heap of Birds discussed here, because he had an installation on my campus in Urbana-Champaign for a while that was incredibly thought-provoking (see below). One of the things I’m learning from reading more books influenced by Ethnic Studies (Genevieve Carpio’s Collision at the Crossroads, Eric Avila’s The Folklore of the Freeway) is the importance of considering artists’ work alongside what social scientists might consider as more traditional academic subject matter.

I really enjoyed this book. I would definitely consider using it in my undergrad class because it’s a perfect combination of how we can look at seemingly minor aspects of the landscape like street signs–something students can do no matter where they are–and then use those elements of the landscape to understand how settler colonialism is an ongoing process that can still be “unsettled” and resisted. At the same time, and most valuable from a theoretical perspective, Brand illustrates in a number of ways how White and Native spaces overlap each other on the same territory, and that this overlap itself is a different kind of spatiality: “Contemporary Native space continues to defy the spatial absoluteness, certainty, and singularity that colonization intends to generate. Native space maintains layered geographies, and provides for coexisting partialities” (p. 97). Getting students to understand these simultaneous ways of seeing space would be a worthy goal in and of itself.