Katherine McKittrick famously wrote that “Black matters are spatial matters” in Demonic Grounds, and Brandi Summers demonstrates that in two interconnected ways in Black in Place: how blackness is employed in placemaking while Black bodies are removed from that same place. These simultaneous processes drive the production of space in the process of gentrifying H Street in Washington, DC. I really enjoyed this book and got a lot out it; I would highly recommend it for urban scholars of any background.

Summers’s book was an interesting companion to David Wilson’s book on Chicago that I read earlier this year. Wilson looked at blues clubs and the tension between their role as community centers and their growing importance as tourist attractions, with gentrification looming on the horizon. Summers addresses a very similar concept in the case of H Street, but she develops an analytical tool to understand it: black aesthetic emplacement. Redeveloping H Street means keeping just enough of its African American heritage visible to make it “cool” and “diverse” and a little bit edgy, while brushing aside the lived history and current inhabitants of this place. She points out the importance of “authenticity” and notes that it’s usually attached to things and experiences, but not people. So a neighborhood is “authentic” if its built environment evokes a certain kind of past, or if newcomers can eat certain ethnic foods, but interacting with the people who produced that built environment is not important.

Black aesthetic emplacement for Summers functions as a kind of diversity indicator, because diversity itself is an aesthetic. Diversity is on the surface, appearing to take in all comers in a harmonious whole, but it ignores the histories and social processes underlying the presence of different groups and what they’re allowed to do in that space. On H Street, Summers argues that Irish and Jewish pasts were unearthed and put on display to demonstrate that this had not always been a Black neighborhood, but that African Americans were just one of many groups who had lived here over the years. That makes it okay for white gentrifiers to move in as just the latest group to inhabit an ever-changing, always-diverse space.

The flip side of black aesthetic emplacement is Black displacement. Actual Black people don’t drive up property values and increase the coolness factor the same way that a black aesthetic does. So as H Street has been redeveloped for white suburbanites to move back into the city, that process has pushed out existing residents not just through higher rents, but through the elimination of the businesses that had managed to remain through decades of disinvestment. Summers shows how city programs to develop small businesses explicitly exclude Black-owned businesses like hair salons and convenience stores in favor of “innovative” shops like Pilates studios and dog boutiques. Unlike my vague, passive voice above about “being redeveloped,” Summers therefore identifies the specific mechanisms by which commercial gentrification occurs.

What I was most interested in, of course, was the relationship to mobility. While the H Street streetcar isn’t a main focus of the book, Summers does discuss the ways in which formal and informal surveillance work to police Black mobilities along H Street. “Diversity” still benefits from the presence of some Black people, but not too many, and only if they’re in motion on the bus rather than socializing on the sidewalk. This comes back around to the aesthetics argument in my favorite line from the book: “Urban should not look suburban but can feel suburban in its visual representation of safety” (p. 116). As a white child of the suburbs who grew up afraid of cities and who acknowledges that even today, I’m only comfortable in some kinds of urban neighborhoods, this really hit home. Actually, the whole book made me think a lot about my past and present relationship to cities, above and beyond its excellent critique of specific elements of gentrification and placemaking.

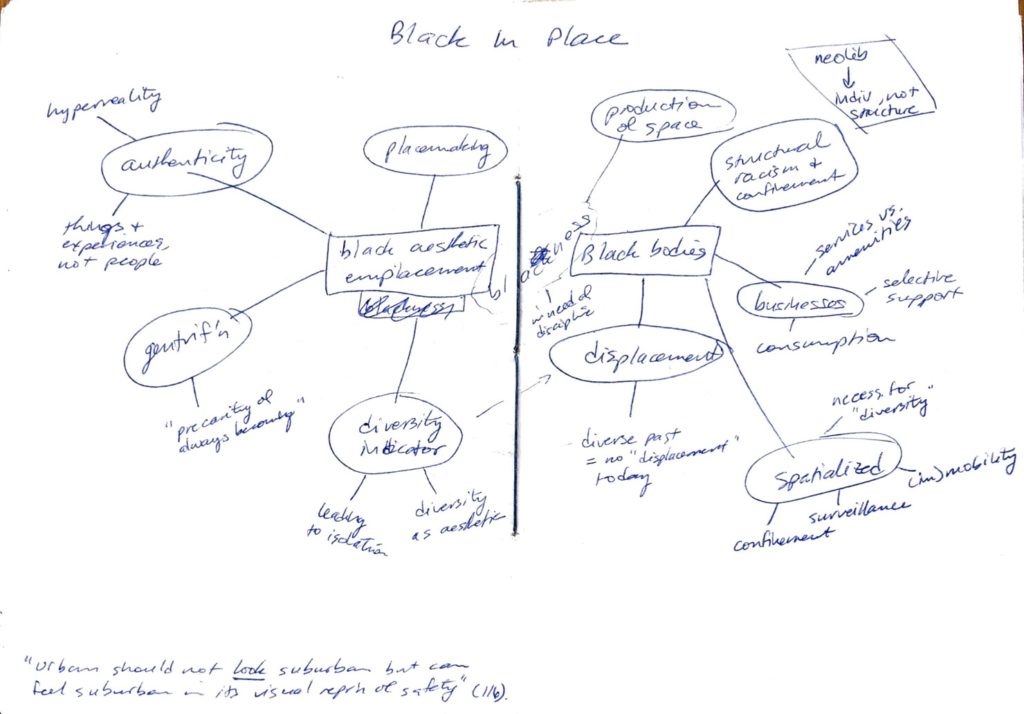

Below is a scan of my mind map of the book, if that might be of interest. I try to do this for most books that I read, either chapter by chapter or for the whole book. (The line down the middle is just the center of the hand-bound book.)